I have a review up at Unreality SF, of the first of last year's trilogy of two-in-one

Doctor Who stories,

Alien Heart and Dalek Soul.

|

Acquired October 2012

Read December 2012 |

A Pair of Blue Eyes by Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy wrote three "scientist novels"; this was the first, preceding

Two on a Tower and

The Woodlanders. It's also the only one of the three not to play a significant part in my book about Victorian scientists in fiction, because I think Hardy has less to say about Henry Knight as a scientist than he does

Two on a Tower's Swithin or

The Woodlanders's Fitzpiers.

Partially, this is because Henry Knight is not actually a scientist. The book was published in 1872-73, before the term "scientist" really took off (it wasn't used in fiction, for example, until Hardy himself described Swithin as a scientist in 1882), but even if the term had been in common use, you wouldn't call Knight one. Knight is the enthusiast of science from the age before professionalism, not even a "man of science" but an intellectual man of the upper classes who has many enthusiasisms, including science; for example, he keeps an aquarium (129), and once the narrator calls him a geologist. (More on that later.) But by occupation he is a barrister (not that he actually does any law), and he is also a writer of essays and reviews.

So there might not be an actual scientist in this "scientist novel," but the novel demonstrates-- as both Hardy in particular and the Victorians in general so often do in writing about scientists-- an interest in perceptions and how they are formed. Right from the start, the narrator refuses to describe the novel's heroine, Elfride Swancourt: "It might vulgarise her, and rob her of some of the sweetness which the stolen glimpses only that will for the present be taken may serve to heighten" (7-8). So right from the first page we see the observing someone intensely, with detail and thoroughness, will rob the observer of insight and truth into that person.

Henry Knight is valorized by his friend Stephen Smith for his insight, but we the readers occasionally see that Knight's perceptions are not all that. Thankfully, Knight himself seems to be aware of this, which is more than you can expect of many unaware people; Knight tells Stephen, "All I know about women, or men either, is a mass of generalities. I plod along, and occasionally lift my eyes and skim the weltering surface of mankind lying between me and the horizon, as a crow might; no more" (131). Knight compares himself to a crow, but I wonder if a scientist (man of science) might not be the better comparison. Darwin published

The Descent of Man just a year before

A Pair of Blue Eyes came out,* and what did Darwin-- or any scientist-- do other than come up with generalities to apply over a wide variety of particular cases based on the occasional skimming? Darwin could not possibly observe

all life, and neither can Knight, and so must induct generalities based on what he

has seen.

That said, Knight is not aware of his own lack of awareness to the extent he claims to be. (A common problem of the unaware, I might argue.) When Knight misjudges Elfride, the narrator chides, "the essayist's experience of the nature of young women was far less extensive than his abstract knowledge of them led himself and others to believe. He could pack them into sentences like a workman, but empirically was nowhere" (173). We even see an extract from Knight's diary later on, where he attempts to generalize from a single anecdote about Elfride to a general conception of women (176), though it's unclear to me to what extent we're meant to buy Knight's understanding of Elfride as correct. But he is definitely a would-be scientist, categorizing and generalizing what he observes into systems.

Elfride's mother posits, though, that people

without such systems actually are better observers; she claims that a

'companionless state will give us, as it does everybody, an extraordinary power in reading the faces of our fellow creatures [...]. I always am a listener [...] – not to the narratives told by my neighbours' tongues, but by their faces – the advantage of which is, that whether I am in Row, Boulevard, Rialto, or Prado, they all speak the same language. I may have acquired some skill in this practice through having been an ugly lonely woman for so many years, with nobody to give me information; a thing you will not consider strange when the parallel is borne in mind, – how truly people who have no clocks will tell the time of day.' (138)

Elfride's father chimes in at this point, suggesting that labouring men learn, because they lack fancy tools, to tell the time or weather much better than those that

do have them. So Henry Knight's system of skimming and inducting may allow him to devise useful generalities, but the uneducated man (or woman) observes more deeply and more closely because he has no other option. Mrs. Swancourt almost comes across as a proto-Sherlock Holmes in her ability to extrapolate from the observed's minute particulars. Deduction, not induction. (I think; I always get them confused.)

Of course, I could spend all day teasing out the relationship between sight and knowledge in

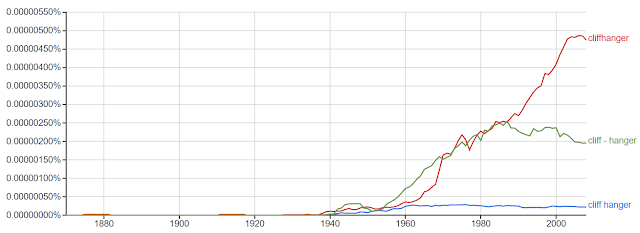

A Pair of Blue Eyes (how perfect is the observation that "Stephen fell in love with Elfride by looking at her: Knight by ceasing to do so" (188)), but I want to turn to the novel's most famous scene, the one that created the word "cliff-hanger" when

A Pair of Blue Eyes was originally serialized in

Tinsley's Magazine. Knight is literally hanging from a seaside cliff by his hands, which Hardy describes in evolutionary terms; Knight is said to hold on "with a dogged determination to make the most of his every jot of endurance" (212), and as he observes the cliffside, we're told it is antagonistic to all "strugglers for life" (213), as there is not even a blade of grass or insect upon it, "strugglers for life" recalling the term "struggle for existence" popularized by Malthus and reluctantly adopted by Darwin in

On the Origin of Species.

Knight's mind goes blank, and he cannot think of his future or his past. Yet he accesses the past anyway-- not his personal past, but his evolutionary past:

opposite Knight's eyes was an imbedded fossil, standing forth in low relief from the rock. It was a creature with eyes. The eyes, dead and turned to stone, were even now regarding him. It was one of the early crustaceans called Trilobites. Separated by millions of years in their lives, Knight and this underling seemed to have met in their death. It was the single instance within his reach of vision of anything that had ever been alive and had had a body to save, as he himself had now. (213)

In a sense, this is astounding. Hardy is one of the first writers of fiction, I would argue, to tap into the new way of seeing that the discoveries of the nineteenth century had to offer. His treatment of scale here reminds me of that of H. G. Wells, except that Wells was using it in science fiction. (Some have argued that Hardy is an sf writer, including Brian Aldiss, and I see what they're getting at, but I feel like it broadens the term to the point of uselessness.) Hardy, like Wells, sees in the million-year timescale of life on Earth, a towering insignificance. Knight might have millions of years on the trilobite, but he's just as liable to die in this cliffside, and just as unable to see anything. Hardy himself would revisit the idea of cosmic insignificance in

Two on a Tower, there demonstrated by the vastness of space, but here it comes from the vastness of time.

Well, kind of. There's only one thing within his field of vision, but Knight turns out to have more scientific training than I gave him credit for earlier: "Knight was a geologist; and such is the supremacy of habit over occasion, as a pioneer of thoughts of men, that at this dreadful juncture his mind found time to take in, by a momentous sweep, the varied scenes that had had their day between this creature's epoch and his own" (214). So all of a sudden he sees the span of history extending backward from him: primitive cavemen, mastodons, iguanodons, flying reptiles, "fishy beings of lower development," all the way to the trilobite. And

then his thoughts rebound to the present and his burgeoning relationship with Elfride.

From here, his thoughts seem to alternate between pondering on his perilous situation and on his hopes with Elfride. Does he love her? Will he survive? These two questions merge into one by the end of his ordeal, I would argue: "he thought – he could not help thinking – that his death would be a deliberate loss to earth of good material; that such an experiment in killing might have been practised upon some less developed life" (217). In this way the cosmic becomes the personal; he will demonstrate his fitness to belong to the evolutionary chain he observed in his mind's eye by surviving and thus (probably) reproducing. If he does not die, then he will be the

next part of the chain.

He

does survive, because of Elfride, who removes her clothes and fashions them into a rope to pull him up off the cliff. In the midst of this, he manages to ogle her in her undergarments: "There is nothing like a thorough drenching for reducing the protruberances of clothes, but Elfride's seemed to cling to her like a glove" (218). So there we have "the male gaze," which is yet another way of seeing the world, and one Hardy is also often attentive to in his writing. But could he have held on, or she risked so much to save him, without the sexual pull between them? Their love and their sexual desire ends up proving his evolutionary fitness. (Well, kind of. Because this is a Thomas Hardy novel the relationship of course does not end well.)

So Knight's scientific perspective, slight though it might be, ends up being his salvation when it merges with his sexual desire. He defies his understanding of his own cosmic insignificance to find a reason to survive, and in doing so, cements his feelings toward Elfride. There's a lot more you could say about this scene, and I think I've gone on enough, but it's a tremendous example of the way the scientific discoveries of the Victorian era reshaped our perceptions and thoughts. Hardy was one of the first to capture that, and one of the best.

* Can we read anything into the fact that Hardy wrote a novel where a woman chooses between male suitors just a year after Darwin argues humanity was unique among the animals because men choose women instead of the other way around?