Here is my last set of Hugo ballots: these are all the book-based categories, including the biggie, Best Novel. I don't think I nominated in any of these categories, but I'm not sure. I really should have made a note somewhere.

Best Novel

[UNRANKED] The Kaiju Preservation Society by John Scalzi / Nona the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir

In previous years, I have made it a rule to read every single novel finalist, no matter what I think I will think of them. In some years this has worked out well for me; despite finding the first book of the

Machineries of Empire just okay, for example, I ended up

really enjoying the second. However, I have read enough John Scalzi to know that I am very much not a fan of what he generally does, and everything I heard about

The Kaiju Preservation Society lead me to believe it was the Scalzi I dislike at his most Scalzi. Similarly, having ranked both

books one and

two of the "Locked Tomb" trilogy (now four books long) in sixth place and finding both unremitting, confusing slogs, it seemed unlikely to me that I would get much out of the third book, nor that I would want to spend a week reading its five hundred pages. So, for the first time, I have foregone reading two finalists. Maybe it will turn out I have missed out on some brilliant work... but I doubt it. (If one of them wins, I will eventually get to it as part of

my project to read all Hugo-winning novels I have not previously read... in 2055.)

I did not like this at all, a mediocre novel with no interesting characters and no stakes and bleh prose. See my review linked above for more.

3. No Award

I try not to be an overdramatic hater, but really, if Legends & Lattes wins, it will be one of those books that makes me question the judgement of my fellow Worldcon members so much that I will wonder why I am even participating in this process.

3. The Daughter of Doctor Moreau by Silvia Moreno-GarciaUp until the last third or so, I thought this was going to slot in above The Spare Man. I wasn't in love with it, but it was doing some kind of interesting stuff. But the revelations near the end and the overly neat ending brought it down for me. Ultimately it came across as an unambitious novel that ought to have been ambitious. Spare Man, I think, largely does what it says it will do, but this does not.

2. The Spare Man by Mary Robinette KowalSometimes ranking almost feels too easy, you know? Like, you want ranking to be a challenge because that means you have a lot of very good books. (Or, well, a lot of very bad ones.) But The Spare Man has a very obvious slot to take. It was not incompetent or annoying, so it clearly goes above No Award, but I also didn't think it came across as one of the best books of the year, or even a great one, so clearly below Nettle and Bone.

1. Nettle and Bone by T. Kingfisher

1. Nettle and Bone by T. Kingfisher

Interestingly, I think Legends & Lattes and Nettle and Bone have a bit in common—even beyond the use of the "[NOUN] & [NOUN]" title format. (I think the Kingfisher was actually Nettle & Bone in the US, but I read the UK edition.) They're both fantasy novels that aim to provide reassurance to the reader in the face of darkness of the world: but while Legends & Lattes does this by having no stakes and mediocre humor, aiming for "heart," Nettle and Bone really does have heart because Kingfisher knows that in fiction, you can only get reassurance by having darkness to be reassured about. Nettle and Bone was an easy favorite for me as soon as I read it.

Best Related Work

6. Buffalito World Outreach Project: 30 Translations of "Buffalo Dogs" by Lawrence M. Schoen

6. Buffalito World Outreach Project: 30 Translations of "Buffalo Dogs" by Lawrence M. Schoen

This book is made up of the English-language science fiction short story "Buffalo Dogs" and its translation into thirty different languages, including French, Italian, Hindi, Tamil, two varieties of Spanish, and Klingon. (Author Schoen is the founder of the Klingon Language Institute, and seems to have done that translation himself.) "Related works" are usually nonfiction, but according to the Hugo guidelines, works must be either "non-fiction or, if fictional... noteworthy primarily for aspects

other than the fictional text..." So we're not being asked to assess the story here, but the project. (Along similar lines,

a new translation of Beowulf was a finalist in 2021, and

ended up winning.) For this to work, I think the paratext would have to make the case that this was a worthy project... but in his introduction, Schoen devotes only about a paragraph to the book itself, and it pretty much just says, "I thought it would be fun, so I did it." Any sense of why this might have been a noteworthy idea, much less an award-winning one, is absent.

On top of that, I found the story in question pretty bad. I know we're not supposed to judge this category on the basis of its fictional aspects, but it's about a hypnotist who abuses his powers to violate people's consent in order to carry out illegal acts for not really any reason at all other than that he is greedy. Wow, what a hero! I also found the worldbuilding pretty unconvincing; it's clearly there to make the story work, but doesn't make sense on its own merits. The cover blurb for the book says, "Maybe, just maybe, the power of the buffalitos will bring us all together and we’ll begin treating one another better," but it's about a guy who goes around treating other people quite horribly! If you want to pick a story to bring the world together, there had to have been a better one. Anyway, I wouldn't give this an award, and I certainly wouldn't give it this one, which is much better aimed at nonfiction in my opinion, if not that of the other nominators.

5. Chinese Science Fiction: An Oral History, Volume 1 by Yang Feng

The Hugo voter packet contains this 402-page book in its entirety... in Chinese. There's also a 24-page PDF in English, but all that has been translated is the table of contents and introductions to each section. The book has seven sections, each interviewing one key figure in Chinese sf. There's not really much for me to judge here as a result, other than the general intentions of the book. In other circumstances I probably would have just left it off my ballot, but it seemed a much worthier winner than Buffalito World despite my lack of access to it.

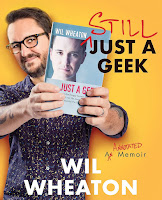

4. Still Just a Geek: An Annotated Memoir by Wil Wheaton

Back in 2004, Wil Wheaton published an edited collection of some of his blog posts with additional linking material to turn it into a coherent narrative under the title Just a Geek. Last year, Just a Geek was republished with extra blog posts, but more importantly, footnotes. These footnotes clarify some stuff from the original book, apologize for bad writing or insensitive jokes, and expand on stuff he didn't say back then, about how his father emotionally abused him and how his mother deprived him of a childhood in her drive to turn him into a child star. I found it a bit of a mixed bag: the "comedy" footnotes were generally not funny and soon got wearying, the ones apologizing for misogynist early 2000s Internet discourse were necessary at first but not at the one hundredth iteration.

I found myself wishing that the material about his parents had been worked in as extra essays; what's frustrating is that the most important one (about the abuse he and his sister went through on the set of the film The Curse) doesn't appear until very late in the book, but it provides important context for a lot of what you've been reading. Aside from this, the best material in the book was generally the original contents of Just a Geek: I liked the discussion of his cameo in Star Trek Nemesis a lot, as well as his interactions with his TNG castmates, which were very sweet. There's a good "found family" vibe to it. But given the best stuff is from 2004, and the new 2022 material—which is what makes this Hugo eligible—is not so great, I find it hard to rank it highly even though I did enjoy it.

This is an essay published on Tor.com, about the history of the so-called "Milford model" of creative writing workshop—people from outside the sf&f field would know it as the Iowa model. It alternates between exploring the history of that model and exploring its repercussions, especially for attendees of the prestigious Clarion workshop from marginalized groups. It's a good piece of writing, but I always find it tricky to rate essays against books in this category. It's probably as long as it needs to be, to be honest, but I think it is beat out by Blood, Sweat & Chrome because that has the depth of being a book. Still, certainly more of interest to say about sf&f than in Wheaton's memoir.

2. Blood, Sweat & Chrome: The Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road by Kyle Buchanan

This is an oral history of the long production of Mad Max: Fury Road, mostly from interviews by the author, with some archival material mixed in. I have actually never seen Fury Road, but found this pretty interesting nonetheless. The long genesis of the film was interesting in particular; I felt that the filming process needed more details on what exactly Tom Hardy's issue was (the book seemed to dance around this), but was still neat, as was the postproduction stuff. Probably I would get more out of the book if I—like the writer and many participants—was convinced of George Miller's genius, but I do like a good making-of book, and this is a decent one.

1. Terry Pratchett: A Life with Footnotes by Rob WilkinsThis is a biography of the Discworld author by his longtime assistant, based on notes Pratchett made toward an autobiography that he never got around to writing. Lots of good details on Pratchett's youth and early career especially; I liked hearing about his working as a journalist and as a press officer for a nuclear power plant in particular. There's also great but devastating insight into his later years, as the cognitive decline of Alzheimer's began to take hold. I did think that at times Wilkins is (for perhaps natural reasons) a bit too into Pratchett's finances and contracts, and I felt like Pratchett's wife totally disappeared from the book, but if you're even a mild Pratchett fan (which is where I would categorize myself) there's a lot to get out of this book. This is a strong work about a key figure in the sf&f field, exactly the kind of thing the Hugo Award for Best Related Work ought to be rewarding.

(Abigail Nussbaum has a very good negative review of the book that I largely agree with... but I still think it's the best thing in the category!)

Lodestar Award for Best Young Adult Book

[UNRANKED] Bloodmarked by Tracy Deonn / Dreams Bigger than Heartbreak by Charlie Jane Anders

Both of these are sequels to previous Lodestar Award finalists. Bloodmarked is a follow-up to 2021's Legendborn, where students at a North Carolina college turn out to be Arthurian knights reborn to fight monsters from another dimension... or something. It did not work for me, and I ranked it fifth. Dreams Bigger than Heartbreak is a sequel to 2022's Victories Greater than Death, a book I almost abandoned halfway through and ended up ranking sixth and one of the very reasons I instituted my "you are allowed to skip a book" rule this year. It seemed very unlikely that the sequels were likely to be serious contenders for me, and so in the interests of time, I skipped them.

5. Osmo Unknown and the Eightpenny Woods by Catherynne M. Valente

This is a fantasy novel about a kid who goes into a magical forest in order to fulfill his role in an ancient treaty between humans and the creatures of the forest. Though I have enjoyed some of Valente's work (she had three works on the Hugo short fiction ballots last year, and they were all strong), too often I am left feeling that if it had been half as long, it would have been twice as good. Most of her books are overnarrated; perhaps in deference to the younger audience, this mostly manages to avoid that (though the narrator is still twee and condescending), but instead fills up the pages with voluminous "funny" dialogue that goes nowhere. At one point the main character gets horns on his head but doesn't know it, and somehow there is a full ten pages of back-and-forth between Osmo being confused at another character saying "what's up with your head?" and someone finally saying "you've got horns!" By about page one hundred, this book had squandered all of its goodwill and I did not care about what anyone was trying to do, but there were another three hundred pages I had to read.

I did like the pangolin character a bit.

4. No Award

Look, other people must like it, but I feel like Osmo Unknown is bad. And it's a kind of bad that annoys me: like Seanan McGuire's, Valente's YA is self-consciously nostalgic in a way I find forced and annoying. Rather than capture what the fantasy of our childhood was actually like, it very archly tries to capture our nostalgia for reading fantasy in childhood—which isn't the same thing at all. Oz may be a fairly whimsical place, but the book doesn't smash your face into this fact, it just gets on with taking the world seriously. I don't believe actual young adults (or middle-graders, which is what Osmo Unknown skews toward in my opinion) would actually like this book. It's for adults nostalgic for when they were supposed to be reading young adult fiction. And this is, you know, a YA award.

3. Akata Woman by Nnedi Okorafor

As noted in my review, I did not find this as successful as the second book in this series. But, you know, it is fundamentally an actual young adult book in my opinion, so it's better than Osmo Unknown and better than No Award.

2. The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik

I had actually read this before voting because I enjoyed the previous book in the series so much. Like Akata Woman, it's the third book in a series where it turns out I liked the second book best. But though it was a bit of a letdown, I still enjoyed it well enough. In another year, though, it's hard for me to imagine this taking second on my ballot.

1. In the Serpent's Wake by Rachel Hartman

Like every other book on the ballot this year bar Osmo Unknown, this is a sequel to a previous finalist, and like every one of those sequels (that I read, anyway), this is not as strong as the book that preceded it. But I think I liked this best of all; honestly, I could go either way between it and The Golden Enclaves, both of which didn't totally deliver on the potential of where the previous installment had left off. I'll give the edge to this because I suspect Novik has the edge with the majority of the electorate, but again, it's hard for me to imagine this being my top choice in any previous year.

Final Thoughts

Last year, I said that Best Novel was the weakest set I'd seen since I began voting in 2017. Well, it got worse! Very frustrating. I don't keep up with current sf&f much beyond reading for the Hugos, so I don't know what those books might be, but Nettle and Bone aside I believe there has to have been five books better than this. I don't have a strong sense of what will win this category; perhaps Nettle and Bone? Kingfisher has done pretty well on the ballot the past few years. Kowal is always popular, but I don't feel like Spare Man is going to be it. It was a bit surprising to see the Scalzi, and I think he has enough detractors I don't think it will be him. Oh god, it's going to be Legends & Lattes, isn't it?

On the other hand, this was a great set of Related Works finalists. I always grumble a bit when they skew away from nonfiction, but here we have five works of nonfiction; I also grumble when they're not books, but here we have five actual books. I think the Pratchett biography will win.

As I indicated above, this was also a weak set of YA finalists. Five of the six were sequels to previous nominees! C'mon, give me something new. I don't have a good sense at all of what might win here. Novik won last year, though some people grumbled about that. (I am not sure why; I think her books are much more clearly YA than whatever Osmo Unknown was supposed to be.)