Writer: Gail Simone

Pencillers: Ed Benes, Adriana Melo, Alvin Lee

Inkers: Ed Benes, Mariah Benes, J. P. Mayer, Jack Purcell

Colorist: Nei Ruffino

Letterer: Steve Wands

Can you go home again? That's the question asked by

End Run, as Oracle, Black Canary, the Huntress, and Lady Blackhawk reunite as the Birds of Prey once more. Black Canary is fresh off of a disastrous Justice League tenure and an even more disastrous divorce... who knows what everyone else has been up to, except that Misfit is sadly nowhere to be seen despite being left in the care of the Huntress in

The Cure. The answer seems to be yes, as we're treated to about eight thousand caption boxes where Oracle, Black Canary, and Huntress express their happiness as the reunion

ad nauseam.

It's also the question asked outside of the comic, as this brings Gail Simone back to the title-- alongside Ed Benes, her original art partner.

End Run provides a decent story, as the Birds battle the mysterious "White Canary," and it seems like some very near and dear to them have suffered because of them. (They have, though not quite in the way they imagined.) The plotline with Oracle trying to figure out what happened to Savant and Creote is probably the best part of this; I found myself less enamored with the Birds' field team being constantly attacked again and again.

For all that parts of this book work, other parts just don't add up. Black Canary is threatened with exposure of her civilian identity... but back in Simone's first run on the title, Dinah actually

published a book about her life as the Black Canary! She also frets over being a murderer like Ollie... you know, the guy who killed a man who killed

millions but is demonized for it for no readily apparent reason. Also, Hawk and Dove join the team, and as to who Hawk and Dove are and why you should care and why Oracle picked them... well, don't look for any answers here. I guess it's because they've got bird-themed names?

(There are captions for the first appearance of each character. Not just in the book, but in every. single. issue. But I've read "Hawk: Avatar of War" six times now, and I'm no closer to knowing what it means or who he is. Cut these things out of the collection, for goodness sake!)

I did like the two-issue story at the end, where Dinah is forced to fight Lady Shiva for the sake of her adopted daughter Sin... only the Huntress has other plans. Any plotline that showcases how awesome the Huntress is is fine by me, and this is definitely one of them.

Like I said earlier, Ed Benes is back, but I'm not sure why. He manages to complete one whole issue; a couple more he starts, and someone else finishes. (I can't tell who, because there's no individual art credits.) Benes, of course, can't draw a picture undefined by the male gaze, but he did good work on this title in the past, and this isn't up to those standards-- his faces are blank and dull and filled with pouty lips. The storytelling is confusing and sloppy, and as always, anyone pretending to be Benes is even worse than Benes. The overly-done coloring seems to work against the whole effect, too.

End Run isn't maybe as bad as this review makes it sound, but it could be a lot better, and I don't of yet see the point of the Birds' breaking up and reunifying. (I'm sure there wasn't one, but still...) This great return hasn't yet convinced me it was worth the effort.

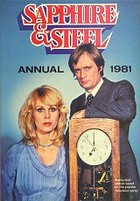

I did like the illustrations, though-- moody and in shadow, they're exactly what every Sapphire & Steel story should look like. Except for the one about the giant robot, where the robot itself has been ripped off of Doctor Who's K-1 robot. On the other hand, the "puzzles" and "informational features"-- one of which is about black holes for some reason!-- are as terrible as you might imagine. (The back cover photo is also a nice one.)

I did like the illustrations, though-- moody and in shadow, they're exactly what every Sapphire & Steel story should look like. Except for the one about the giant robot, where the robot itself has been ripped off of Doctor Who's K-1 robot. On the other hand, the "puzzles" and "informational features"-- one of which is about black holes for some reason!-- are as terrible as you might imagine. (The back cover photo is also a nice one.)