This final post covers my votes in the three Hugo categories for book-length works: novels, graphic stories, and nonfiction. If I did a full review of a work, I'll link to that here. (Note that if you're reading this before 22 August, not all of those full reviews will have gone live yet.) I only did that if I owned the book: I didn't do it for anything I read an e-version of from the Hugo voters packet, or borrowed from the library (as in the case of

Princess Diarist). If the work is freely available on-line, I'll link to that. (Thankfully there is no work of which both of those things is true.)

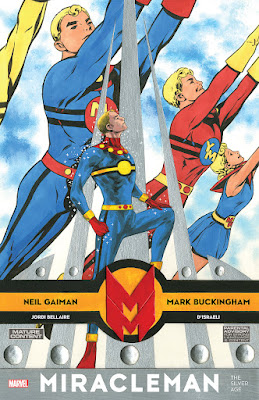

Best Graphic Story

6. Black Panther: A Nation under Our Feet, Book One, script by Ta-Nehisi Coates, art by Brian Stelfreeze

I wanted to like this, and possibly I

will like this. The four issues collected here are clearly just the opening act of a larger story;

A Nation under Our Feet is apparently slated to run across three volumes of

Black Panther. But what's here is alienating, assuming the reader knows more about Blank Panther backstory than I did. What happened to Black Panther's sister, and why doesn't he have any control over his own country? Or, if this stuff

isn't preexisting backstory, it's just alienating. There are definitely some neat things going on here. I liked the sense of Wakanda as a real place with factions and tensions and multiple competing histories, and I liked the two lesbian warriors who go rogue (though no one properly explains what is the organization they went rogue

from), and Stelfreeze occasionally does some really arresting stuff with his visuals, and the idea that a superhero whose core identity is being a super

king has to confront a popular revolution is cool, and leads to good quotations about power and leadership. But at times this book felt like epigrams strung together with imagery, not a story.

5. Monstress: Awakening, script by Marjorie Liu, art by Sana Takeda

In the discrete story stakes,

Monstress is somewhere above

Paper Girls and below

Ms. Marvel. Events come to a climax, but there's clearly a much bigger story we're only beginning to see. But what a story. Sana Takeda's art is absolutely gorgeous, a pointed contrast to the often horrific events it depicts. In a fantasy world inhabited by five races-- humans, gods, Ancients, Arcanics (human/Ancient hybrids), and talking cats-- a seventeen-year-old Arcanic girl goes into the dark heart of humanity to root out the secret of her own existence, something relating to the Old Gods. There's sometimes too much to keep track of, but the core characters are pretty great; I particularly enjoy Maika's friend the world-weary cat Ren, and also I have a lot of affection for the improbably cute fox Arcanic, Kippa. Lush stuff, and a series I will definitely continue to read. If it loses out to

Paper Girls, it's only because

Paper Girls just hits my buttons in a way this does not, as I tend more toward sf than fantasy.

4. Paper Girls 1, script by Brian K. Vaughan, art by Cliff Chiang

A group of bicycle-riding children living in the Midwest in the 1980s encounter something out of this world. I guess 2016 was a bit of a moment for this-- it's like

Stranger Things but with preteen girls. Anyway, this was good: funny at times, horrifying at others, inventive in the way that Brian K. Vaughan often is of late (I mean, I liked

Y: The Last Man a lot, but this and

Saga show that he's upped his game since), and Cliff Chiang is one of my favorite comics artists, so I'm happy to see him show his stuff on something creator-owned instead of being relegated to

Green Arrow and Black Canary or whatever. This is clearly the first chapter in a larger story, not a story complete in itself, which partially motivates my placement of it here. Stands on its own more than a volume of

Black Panther but less than one of

Ms. Marvel. I don't have a problem with that in a general sense, it's one of the things that attracts me to the whole serial comic book medium, but will Vaughan and Chiang stick the landing? I want to know that before I praise it too effusively. I guess this is a limitation of the Best Graphic Story category I don't know of a way to overcome, except maybe in renominating the entirety of

Paper Girls as complete work whenever it comes to a conclusion.

3. Saga, Volume Six, script by Brian K. Vaughan, art by Fiona Staples

I ended up being very torn about the relative rankings of the two Brian K. Vaughan comics, and torn about potential tie-breakers: do I break the tie by going with a return to a world I enjoy? Or do I count inventing something new as superior? In the end I decided that I could appreciate

Saga, Volume Six more than

Paper Girls 1 because there's a coherent story and thematic unity about prisons (the ones we're put in and the ones we put ourselves in) in volume 6 of

Saga, while

Paper Girls feels more like it just stops without resolving story or theme. Plus it might just be the familiarity that makes me like the

Saga characters more, but that's still something, and I'm going with it. There are no cute walrus farmers* or exiled robot princes in

Paper Girls.

2. Ms. Marvel: Super Famous; script by G. Willow Wilson; art by Takeshi Miyazawa, Adrian Alphona, and Nico Leon

Ms. Marvel is one of two comics I buy on a monthly basis, so this was actually the only finalist in this category I'd read already; I brushed back through the issues (vol. 4, #1-6) instead of rereading the whole thing. In the two story arcs collected here, Kamala fights gentrification in Jersey City (it turns out to be a HYDRA plot) and accidentally creates an army of duplicates of herself. There's a lot of good teen stuff here: learning how to deal with friends in romantic relationships, learning how to find your limits, learning how to deal with family members in romantic relationships. The second story is in particular just brilliantly hilarious; Nico Leon draws an amazing army of Ms. Marvel duplicates, and the bit where Kamala's friend Bruno summons Loki is delightful.

Ms. Marvel is one of the best things going right now in superhero comics. The only bad thing about this volume is that Adrian Alphona, who drew most of G. Willow Wilson's original run, only draws ten pages of it. I have actually liked Takeshi Miyazawa since

Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane, but Alphona defined Kamala and her world, and I'm sad that as it's gone on, he's drawn less and less of it for whatever reasons.

1. The Vision: Little Worse than a Man, script by Tom King, art by Gabriel Hernandez Walta

It was a tough choice for me between

The Vision and

Ms. Marvel, but I guess in a tie I give the pip to the first volume of something new over the fifth volume of something not quite as new.

The Vision places the Avengers' best synthezoid in the D.C. suburbs with a newly constructed family (one wife, two kids) as he takes up a new job as the president's Avengers liaison. Things quickly get out of control, though, as the Visions are subject to prejudice from the locals and assault by supervillains in suburbia. King is a brutal, economic writer (if I'd been a supporting member of Worldcon earlier, I'd've nominated his excellent

Omega Men run) who brings something really special to the way he tells this story (great captions!), and Gabriel Hernandez Walta matches his sensibilities, with a simple style that belies the brutality underneath this world (

our world) and a great way with facial expressions. Walta's Visions hit the uncanny valley perfectly.

Best Novel

6. Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee

This was the only Best Novel finalist I just completely bounced off of-- I enjoyed everything ranked above it to varying degrees, but I just could not get into this book. That said, I wouldn't

object if it won; it seemed like the kind of book that could be someone else's cup of tea (and it must have been many people's cup of tea to end up a finalist), but it very much was not mine. Too frustrating and inexplicable to be interesting or enjoyable.

5. Death's End by Cixin Liu

The top three books were hard to rank; the bottom three much more easy. Though

Death's End probably has more of sfnal interest than

A Closed and Common Orbit, sf is about more than neat ideas-- a good novel also needs a compelling story or stories, and

Death's End did not, whereas as I got emotionally involved in

A Closed and Common Orbit... despite not wanting to! And the ideas in

Death's End just weren't as interesting as those in the first two

Remembrance of Earth's Past novels in any case. If all three books had been as good as

The Three-Body Problem, I could see this ending up higher on my ballot, but

Death's End was

not as good as the first two, so oh well.

4. A Closed and Common Orbit by Becky Chambers

Even if I did end up getting a bit misty-eyed while reading

A Closed and Common Orbit, and even if it provides a complete adventure in a way that

The Obelisk Gate and

Too Like the Lightning it did, it's still hard for me to claim that it's

better than those books. I mean, it's very good, but if science fiction should invent new realities for the purposes of thought experiment (and though that's just one thing it does, but it's an important one to me),

A Closed and Common Orbit is just not as ambitious as the other two. It's a strong slate that could push a book this emotional this far down, I think.

3. The Obelisk Gate by N. K. Jemisin

I found this tough to rate versus

Too Like the Lightning, I think partially because both are incomplete works--

The Obelisk Gate is reasonably satisfying on its own, but it is pretty clearly the middle chapters of a longer story, meaning that in some sense it will have to be judged retrospectively, once I have complete information on how that longer story succeeds. But I did really like it regardless.

2. All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders

I will note that this is, like, impossible.

All the Birds and

Obelisk Gate and

Closed and Common and are all three very strong books that did not nail things 100%. Each book has elements that makes it award-worthy, and aspects that hold it back no matter how great it is. I ended up ranking

All the Birds here because I felt like it satisfied me more than

Obelisk Gate, yet lacked the ambition of

Too Like the Lightning. On a different day I could probably totally rejuggle everything under my first-place choice and still be satisfied with the resultant list.

1. Too Like the Lightning by Ada Palmer

Though this is no more a complete story than

The Obelisk Gate, possibly even less so as the book doesn't really have an ending, kind of just coming to a stop that will be picked up in

Seven Surrenders,

Too Like the Lightning feels like the greater achievement to me, in that Jemisin is revisiting a world (even if she is fleshing it out in doing so) while Palmer is establishing a new one, and quite successfully at that.

Best Related Work

7. Women of Harry Potter by Sarah Gailey

Not actually a book (I guess a "related work" doesn't have to be but usually is), but a series of blog posts on Tor.com, five as of the end of 2016 (six now), discussing female Harry Potter characters. Gailey doesn't write academic-style criticism; these are

very enthusiastic tributes more than anything else, which often felt like they reflected what fans

want the characters to be like more than what they actually

are like. Well written, I guess, but they left me cold.

6. No Award

I'm having a hard time justifying the idea that the Hugo Award would go to a series of five so-so blog posts. (Kameron Hurley won the category in 2014 for a single blog essay, but that essay was much better than any of these.) On the other hand, even though I didn't like

Traveler of Worlds very much, I can see how someone

might like it, so I ranked it higher than No Award.

5. Traveler of Worlds: Conversations with Robert Silverberg by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

If you hang on to Robert Silverberg's every word, this might be the book for you. It's hard for me to imagine why you would, though, as I found the questions and answers here largely superficial. Zinos-Amaro rockets through scintillating questions such as, what kind of food does Silverberg like to eat? and how does he organize his day? But even when Zinos-Amaro asks interesting questions, Silverberg largely fails to answer them interestingly; a big deal is made about Silverberg's travel and how it broadened his mind, but when Zinos-Amaro asks for an example, the best Silverberg can do is to explain that he got lost once and his wife's iPhone's GPS saved them, so he learned smartphones aren't that bad. Whoa! It also would have been nice if Zinos-Amaro had edited out the bits where he asked Silverberg a question and Silverberg said he had no opinion on the topic. Plus Silverberg goes on rants about how people in their thirties have no manners when they eat out. Scintillating! I haven't read much of Silverberg's fiction (no novels, just a few short stories); possibly if you did, you would like this more than me. Silverberg rags on Thomas Hardy for a few pages and, well, I know who I think will endure in that contest.

4. The Princess Diarist by Carrie Fisher

This book collects a diary Carrie Fisher kept during the filming of

Star Wars in 1976, a mix of poetry and prose written about her relationship with Harrison Ford, framed by Fisher's take on that relationship now. Interesting enough for what it is, and I suppose it's nice to have story out there-- but there's actually not much of a story

there. Ford was in his mid-thirties and married and away from home (

Star Wars was filmed in the UK), while Fisher was nineteen and acting more worldly than she actually was, and they had sex on the weekends but little connection-- Fisher was kind of in love, but then they flew back to the United States and it was all over. There is the occasional real interesting moment, like an incident where she really connects with Ford when she flawlessly imitates his walk. Fisher's thoughts on the way Leia and the

Star Wars phenomenon shaped her life are interesting, though it would have been nice to have heard more about her returning to the character for

The Force Awakens, which she only alludes to. Like a lot of the book, though, this section feels padded, as if Fisher is vamping to fill up space to justify this being its own volume. It's quite short, but it's still too long.

3. The View from the Cheap Seats by Neil Gaiman

This was a fun collection of various pieces of nonfiction Gaiman has written across his career, ranging from 1989 to 2016. It's a hodgepodge (or an olio as the

LA Times crossword might say) of speeches, introductions, newspaper columns, and all sorts. There's a lot to like here: Gaiman is a lively, engaging writer, enthusiastic in his appreciations, and usually humorous. There are only so many introductions you can read in a row, though, especially as Gaiman comes across as vaguely skeptical of the whole concept of the introduction, but my main takeaway from reading this was how invested Gaiman is not just in the genre of speculative fiction, but its fandom and its fans. We could do a lot worse. (Also, his thoughts on genre contrast in interesting and productive ways with Le Guin's below.)

2. The Geek Feminist Revolution by Kameron Hurley

A collection of essays on topics related to feminist geekdom, some previously published (mostly on the author's blog), some original to the book. The very best one is

an analysis of masculinity in True Detective, which really effectively blends the critical, the personal, and the political in a way that illuminates both

True Detective and general cultural trends. I also really liked the last essay,

about llamas as a metaphor for how stories shape our perceptions of history. If they had all been as good as those two (and some others were), this would have got my top spot, I think, but Hurley has a tendency to wax in generalities that prevents her from being as insightful as she might.

1. Words Are My Matter by Ursula K. Le Guin

I'd place this book almost on a par with Gaiman's collection, as they're pretty similar works. What gave Le Guin the edge for me was its focus (at over 500 pages I eventually got tired of Gaiman's ideas in a way I didn't with Le Guin's 300) and her book reviews, which are more critically successful than anything in Gaiman's book, as fun as it was to read.

Overall Thoughts

I feel like both Best Graphic Story and Best Novel were very strong categories this year. I remember looking at some shortlists a few years ago when Best Graphic Story was first being implemented and being flabbergasted at the abysmal quality of some of the stuff; though I didn't like

Black Panther, I can see how someone else might, and the other five works ranged from very good to great in my estimation.

Similarly, I'd be pleased if anything in my top four won in Best Novel; I thought they were all great books in very different ways, and ranking the top tier especially was completely impossible. Space opera, epic fantasy, utopian sf, hybrid speculative fiction-- all very different breeds of genre fiction, but all doing what it ought to do best. I look forward to reading the follow-ups to

A Closed and Common Orbit,

The Obelisk Gate, and

Too Like the Lightning. My guess is that

Too Like the Lightning or

All the Birds will win, but I think it will be tight.

Related Work I enjoyed the least of these categories. Le Guin is great, of course, but if the other two book categories are pushing the genre forward in new and interesting ways, there's something retrograde about a category dominated by authors who came to prominence in the 1950s (Silverberg), the 1970s (Le Guin), and the 1980s (Gaiman), and one who's famous for being in a movie. I mean, this category is always going to be backward-looking by nature, but I don't feel like it needs to be

this backward looking.

In Two Weeks: I react to the actual award winners, and also sum up my thoughts on this whole Hugo process.

* A walrus who farms, not a farmer of walruses.