What follows is an incredible investigation into George Eliot and the vagaries of nineteenth-century British income tax law, and a demonstration of how far I will go in order to work out something that might not be worth knowing.

I. The Saga Begins

Let me set the scene by explicating a part of

Middlemarch.

Middlemarch is, of course, George Eliot's nineteenth-century realist triumph. It concerns many things, but among them are Tertius Lydgate, a physician, amateur microbiologist, and would-be medical reformer; Dorothea Brooke, a would-be social reformer derided for her lack of systematic observations; and Edward Casaubon, a scholar attempting to systematize all mythology and produce

The Key to All Mythologies. Given my interests in scientists and scientific observation in the Victorian novel, you can imagine that there's a lot for me to work with in

Middlemarch.

|

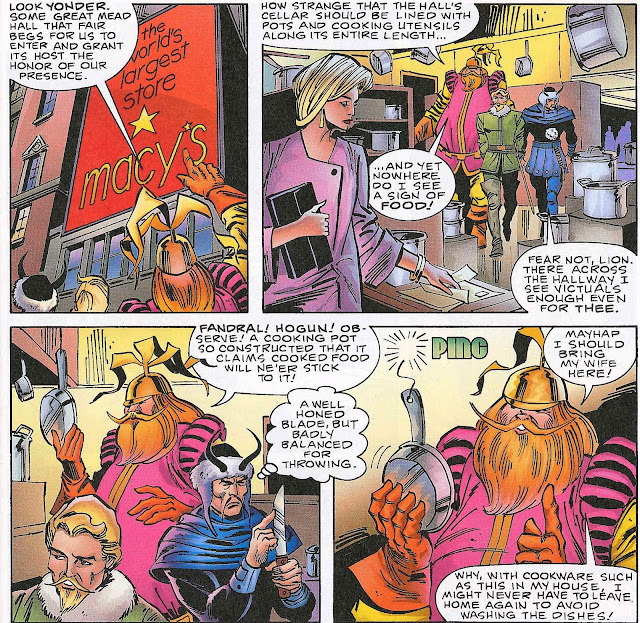

| "Active voracity, my foot." |

Key to my arguments about

Middlemarch is Eliot's use of scientific metaphors, since she uses them (I argue) to suggest the futility of creating accurate observations of individual human beings. In one scene, the narrator ponders on this difficulty in the context of the actions of one Mrs. Cadwallader, the town gossip. He says: (I apologize for the length of the quotation, but this is what you get with Eliot, though I've bolded the most relevant part)

Was there any ingenious plot [in Mrs. Cadwallader's actions], any hide-and-seek course of action, which might be detected by a careful telescopic watch? Not at all: a telescope might have swept the parishes of Tipton and Freshitt, the whole area visited by Mrs Cadwallader in her phaeton, without witnessing any interview that could excite suspicion, or any scene from which she did not return with the same unperturbed keenness of eye and the same high natural color. In fact, if that convenient vehicle had existed in the days of the Seven Sages, one of them would doubtless have remarked, that you can know little of women by following them about in their pony-phaetons. Even with a microscope directed on a water-drop we find ourselves making interpretations which turn out to be rather coarse; for whereas under a weak lens you may seem to see a creature exhibiting an active voracity into which other smaller creatures actively play as if they were so many animated tax-pennies, a stronger lens reveals to you certain tiniest hairlets which make vortices for these victims while the swallower waits passively at his receipt of custom. In this way, metaphorically speaking, a strong lens applied to Mrs. Cadwallader's match-making will show a play of minute causes producing what may be called thought and speech vortices to bring her the sort of food she needed. Her life was rurally simple, quite free from secrets either foul, dangerous, or otherwise important, and not consciously affected by the great affairs of the world. (59-60)

So my argument about this is essentially that this metaphor suggests that observing the actions of human beings is incredibly difficult: we draw the wrong conclusions about the source of their movements, just as a scientist would if they looked at a creature ostensibly exhibiting an active voracity without a powerful enough lens. But the observational power necessary to create an accurate observation of Mrs. Cadwallader is immense-- it takes the novelist three full pages to explicate why she does what she does, and of course the novelist has much more access to Mrs. Cadwallader's interiority than any of us can ever hope for!

II. A Twist in the Tale

And there my insights would have forever remained if it wasn't for a comment from one of my advisory committee on my dissertation. She highlighted "animated tax-pennies" and wrote: "What do you make of the analogy with taxation? It seems to suggest that the micro and macro levels of phenomena—biological science and political economy--and thus of observation and analysis, could function analogously."

Well! Wasn't "animated tax-penny" just a fancy word for a magnetized coin? I'll show you, committee member. So I attempted to figure out from where I knew this. In my Penguin Classics edition of

Middlemarch, edited by Rosemary Ashton, "tax-pennies" is marked with an end note, which reads, in full, "magnetized coins" (841n38). So I imagined this as coins dancing around under the influence of a magnet-- a nice metaphor for seemingly unmotivated movement actually having a scientific cause. But some cursory Internet searching and then some in-depth Internet searching revealed no indications that an animated tax-penny was a magnetized coin.

Indeed, the only place I can find in the universe of the web or print that refers to animated tax-pennies as magnetized coins is a doctoral dissertation by Catherine Jane Massie, which discusses the same metaphor: "Seen with one lens power a microscopic specimen seems to vacuum in its prey as if these smaller protozoa were magnetized coins ('animated tax-pennies'), but a stronger lens power will 'reveal' the existence of the specimen’s tiny moving hairs, or cilia, that perform the work for the passive larger 'creature'" (156). But she cites no source and uses the same term as the Penguin Classics edition, leading me to believe that she's pulling from it as well.

At the suggestion of a colleague, I reached out to the editor of the Penguin Classics edition, Rosemary Ashton, herself. Professor Ashton indicated that she took the definition from the previous Penguin edition of

Middlemarch, and could not provide any elucidation beyond that. Nothing in the OED or other sources provided a definition of the "animated tax-penny." I should note that nineteenth-century pennies were made of copper-- which is not magnetic.

III. The Plot Thickens

|

Who put him in charge

of metaphors, though? |

The metaphor is cited in a book by J. Hillis Miller about

Middlemarch (and

Adam Bede). Miller singles it out as unusual:

When the little creatures seen under the microscope are compared to "so many animated tax-pennies," a monetary metaphor adds itself to the first one in a metaphor of a metaphor no longer directly grounded in the first level of reality of the novel. The effect of this is odd. It cannot be easily evened out in a total accounting of the interplay of literal and figurative language in the novel. As Wallace Stevens says, "There is no such thing as a metaphor of a metaphor." (97)

But as Miller goes on to show, this

is a metaphor of a metaphor. (He provides a very nice close reading of it, in fact.)

But what

is a tax-penny, then? As opposed to non-tax-pennies, specifically, I mean. Miller goes on to say that the word penny was used to "indicate 'the sum exacted by a specific tax or customary payment.' The word existed in such compounds as 'earnest penny,' 'ale-penny,' or 'fish-penny,' as well as in 'tax-penny'" (102). Well, there you go then, but I want to suggest some modifications to Miller's explanation.

IV. The Truth Revealed

Searching Google Books' nineteenth-century corpus for "tax-pennies" turns up very few references that aren't people just quoting Eliot's use of the term in

Middlemarch. In fact, it turns up three, two of which actually use the term "income-tax pennies." If you search Google Books for "income-tax penny" in the

singular,

suddenly more pop up. Not a ton more (there are seven hits, but one's a duplicate), but enough to get a feel for what's going on, as they use terms like "Mr. Gladstone's own income-tax penny" or "the additional income-tax penny." With these clues, I dug up the following information.

|

| "I'll tax you, and you'll like it." |

William Gladstone, later to become prime minister (1868-74, 1880-85, 1886, 1892-94), became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1852. Whether or not the nation's income tax should be renewed at the time was a big point of contention. Gladstone argued that the income tax should be renewed but gradually phased out (Seligman 154-5). As you might imagine if you know anything about "temporary" taxes, though, the phasing out did not take place. The Crimean War (1854-56) necessitated the raising of taxes, in fact. Edwin Seligman records the following 1862 exchange in Parliament:

"Necessity," said Gladstone, "drove us to it in 1842, and necessity has attached us to the use of it." And when he was interrupted by cries of "no! no!" he added: "When I use the word 'attached' I mean not as a bridegroom is attached to his bride, but as a captive is attached to the car of his conqueror." (157)

Far from phasing out the income tax, Gladstone had been captured by it. One of the specific increases that Gladstone created was in 1860, from 9 pence to 10 (or from 9

d. to 10

d., as the British say) (Seligman 156). This, then, is Gladstone's income-tax penny. I think Eliot is probably picking up this term when she uses the phrase "tax-pennies" in

Middlemarch, though somewhat adapting it, as it's usually used in the sense of an institution, not as referring to individual pennies paid in tax.

V. Happily Ever After

|

| Pictured: Mrs. Cadwallader |

What can we conclude about Eliot's metaphor from all this research? Well, I think-- that as my committee member's comment indicated-- she's analogizing Mrs. Cadwallader's observations to two different kinds of scientific observation: on the microscopic scale (as in microbiology) and on the macroscopic scale (as in political economy). In both of them, the tracing of causes is difficult and complex. You might assume the microscopic organism has an active voracity when in reality it's using tiny hairlets to draw in its victim, and you might assume the tax-pennies are animated when in reality it's British tax system that causes them to be deposited with a collector.

Like I said, Miller quotes Wallace Stevens to say a metaphor oughtn't have its own metaphor, and Miller's argument about this passage is that Eliot is highlighting the trickiness of using metaphor as a descriptive tool; he says it models "the unanswerable question of whether the making and movement of signs is active or passive, controlled by human beings or controlling them. It is both and neither" (102-3). Eliot

does address this theme previously in

Middlemarch in the passage where the title of this blog post comes from: "for we all of us, grave or light, get our thoughts entangled in metaphors, and act fatally on the strength of them" (85).

This is a generous reading. A contemporary reviewer of Part I of

Middlemarch in

The Athenæum was less kind; they quoted this same passage and then commented:

Metaphors such as these, far-fetched, somewhat strained, and drawn by force from the most recondite arcana of chemistry and zoology, are apt, if indulged in, to degenerate into mannerism. We do not remember such in 'Romola'; but 'Middlemarch' is full of them. They choke the mechanism of the English, and they interrupt the thought. George Eliot ought to be far too self-possessed to fall away into any such tricks of style. (714)

Ouch.

Works Cited

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. 1871-2. Ed. Rosemary Ashton. London: Penguin, 2003. Print

Miller, J. Hillis. Reading for Our Time: Adam Bede and Middlemarch Revisited. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

Rev. of Middlemarch: a Study of Provincial Life, Book I—Miss Brooke. Athenæum 230 (2 Dec. 1871): 713-14.

Seligman, Edwin R.A. The Income Tax: A Study of the History, Theory, and Practice of Income Taxation at Home and Abroad. New York: Macmillan, 1911.