For Christmas, my wife got me the two Loki Modern Era Epic Collections from Marvel, which collect Kieron Gillen's acclaimed run on Journey into Mystery. I already owned Gillen's Thor run, so I was going to read those three collections, and then go from them into Gillen and Jamie McKelvie's Young Avengers run, where Loki appears as well; I've had the omnibus of it since it came out in 2015, but never gotten around to it.

But I didn't want to read the second Young Avengers without doing the first; I borrowed part of that from the library way back when and enjoyed it a lot, and have always intended to pick up a complete collection of it. And if I was going to read both Young Avenger runs, which feature the Kate Bishop Hawkeye, surely this was the time to read both the Matt Fraction/David Aja and Kelly Thompson/Leonardo Romero runs on Hawkeye, both of which I've long been interested in!

So what soon emerged was one of my characteristically long and complicated comics reading projects, which will take in stories featuring the Young Avengers, Loki, and Hawkeye from Young Avengers vol. 1 (2005-06) to Hawkeye: Kate Bishop (2022), with fourteen stops along the way. The first of those is the first half of the omnibus of the original Allan Heinberg/Jim Cheung Young Avengers run:

Young Avengers by Heinberg & Cheungstories from Young Avengers vol. 1 #1-12, Young Avengers Special #1, and Civil War: Young Avengers & Runaways #1-4 |

|

Collection published: 2022

Contents originally published: 2005-06

Acquired: June 2025

Read: July 2025

|

Writers: Allan Heinberg, Zeb Wells

Pencilers: Jim Cheung, Andrea Di Vito, Michael Gaydos, Gene Ha, Jae Lee, Bill Sienkiewicz, Pasqual Ferry, Stefano Caselli

Inkers: John Dell with Drew Geraci and Dave Meikis, Drew Hennessy, Andrea Di Vito, Michael Gaydos, Gene Ha, Jae Lee, Bill Sienkiewicz, Pasqual Ferry, Jim Cheung, Rob Stull & Dexter Vines, Jay Leisten, Matt Ryan, Jaime Mendoza, Livesay, Mark Morales, Stefano Caselli

Colorists: Justin Ponsor, José Vilarrubia, Art Lyon, June Chung, Dave McCaig, Daniele Rudoni

Letterer: Cory Petit

The first thirteen issues here are the original twelve-issue run of Young Avengers plus the Young Avengers Special, which are entirely written by Allan Heinberg and mostly illustrated by Jim Cheung (he pencils everything but #7-8 and the special). I think it's a masterclass in how to set up a bunch of a new characters in a preexisting universe and instantly get the reader to actually care about them. The opening six-issue story is about the Avengers (who have been disbanded at this point in time) discovering the teenagers the press has dubbed the "Young Avengers" are running around and deciding to stop them; specifically, the story focuses on Captain America, Iron Man, and Jessica Jones. We discover the mystery of the Young Avengers along with them, as they uncover who these characters are—Patriot, Iron Lad, Hulkling, and Asgardian (later "Wiccan")—and then as two more end up joining the team—Hawkeye and Stature.

As "Young Avengers," I think Heinberg and Cheung were particularly clever about their backstories because mostly, they are not obviously linked to whom they seem to be linked. Hulkling isn't a mini-Hulk but a shapeshifter (we find out in a later story arc that he's half-Skrull); Wiccan isn't actually an Asgardian but a sorcerer; Iron Lad looks like Iron Man but is actually using the futuristic technology of Kang the Conquerer. At first it seems like only Patriot is who he seems to be, the grandson of Isiah Bradley, the original, black Captain America, but we even eventually discover that his powers don't have anything to do with his grandfather. (When I first read this story, by the way, I had never read Truth: Red, White & Black, so rereading having done so gave me a lot of helpful context. There's even a brief mention of Josiah X from The Crew, who is Patriot's uncle.)

|

Not pictured: the Crew callback. You can't say Allan Heinberg doesn't love his Marvel universe, but I really appreciate that he loves all of it, not just the stuff he would have read as a kid.

from Young Avengers vol. 1 #3 (script by Allan Heinberg, art by Jim Cheung & John Dell) |

But the characters aren't just successful in continuity terms—otherwise I don't think

Young Avengers would have become the long-lasting series it is. Rather, every one of them leaps off the page as

people with personalities. Patriot's earnestness but also lack of self-confidence, Iron Lad's determination not to fulfill his destiny, Hawkeye's playfulness and authority, Stature's lack of confidence, and so on. I basically loved all the characters right away, though I particularly liked Hawkeye, Stature, and Patriot. Patriot (Eli Bradley) I've discussed already, but I do like his determination to overcome his own powerlessness (even if I am a bit skeptical to the decision to make the one black character the one who is using drugs!) and do the right thing.

Kate Bishop as Hawkeye is fun right from the off: powerless like Patriot, but unlike him, confident in her abilities, taking down bad guys in the middle of her sister's wedding while wearing a bridesmaid's outfit and deciding to become a superhero right there on the spur of the moment. You can see why she became a breakout success.

|

I like that it's the two team members who joined late to keep the team going after Iron Lad "quits"; it's a nice touch.

from Young Avengers vol. 1 #6 (script by Allan Heinberg, art by Jim Cheung & John Dell, with Dave Meikis & Jay Leisten) |

I also really like Cassie Lang as Stature. She's the daughter of Ant-Man, and she aspires to heroism, but has spent her childhood largely isolated from her (dead) father, with a mother who wants her away from that life, and a cop stepfather who still sees her dad as the criminal he used to be. Like her father, she can control her size, shrinking and growing; it's the kind of on-the-nose metaphor that works so perfectly in superhero comics, that makes them what they are: this girl who feels like she's nothing can literally become nothing, but can also finally make herself seen.

|

I like Iron Lad a lot, which makes it a shame that the very nature of the character basically makes it impossible to use him in any stories other than his first one.

from Young Avengers vol. 1 #5 (script by Allan Heinberg, art by Jim Cheung & John Dell) |

This first six issues are a single story, "Sidekicks," about the Young Avengers coming together and trying to avert Iron Lad's future as Kang the Conqueror. It's a great story, about what we have to do to avoid becoming who we're afraid we might be, and how sometimes we have to take steps we thought we never could. Cheung is a great artist, able to do action and character. I'm surprised he hasn't done more big stories than this, he seems like he ought to be one of the greats. (Maybe I'm wrong and he has.) Justin Ponsor also does great stuff on colors, manipulating tone and atmosphere effectively—the story is bright when it needs to be, gloomy when it needs to be, and he brings out the facial details really well.

The weak part in the first twelve issues is thus, not surprisingly, the second story illustrated by Andrea Di Vito, "Secret Identities": he just doesn't have Cheung's command of character in a story that really needs it. Other than that, the story is fine; this is where we learn that Patriot didn't really inherit anything from his grandfather, but rather is using "mutant growth hormone" to give himself powers. But he also learns that he can be strong without it.

|

I miss Jessica Jones. Maybe I should have added my unread Alias Omnibus to this project? ...no, cut it out!

from Young Avengers Special #1 (script by Allan Heinberg, art by Michael Gaydos) |

After this is the Young Avengers Special, where Jessica Jones interviews all the Young Avengers; we get a frame story illustrated by Jessica's co-creator, Michael Gaydos, and then short flashback tales for each of the Young Avengers by a variety of artists, including greats like Gene Ha and Bill Sienkiewicz. They're small but strong moments, deepening our understanding of these great characters.

Then comes the final story of volume 1, "Family Matters," where the Super-Skrull comes looking for Hulkling... because it turns out that Hulkling (Teddy Altman) is half-Skrull, half-Kree, and the rightful emperor of the Skrulls! It's a good set-up for a story, but I found the death of Teddy's mother an overly gratuitous moment that seems ultimately self-defeating: surely there was good drama to be mined from the revelations here, and surely this is a kind of trauma the series ultimately won't be able to cope with; it'll just be downplayed unrealistically. Dude saw his mother burnt to death right in front of him!

|

Surprisingly

optimistic takeaway for a kid whose mother was just brutally murdered

hours earlier. He's weirdly chummy with the Super-Skrull!

from Young Avengers vol. 1 #11 (script by Allan Heinberg, art by Jim Cheung & John Dell, with Jay Leisten, Jamie Mendoza, & Livesay) |

This is also the story that introduces "Speed," Tommy Shepherd, who is apparently the twin brother of Wiccan (Billy Kaplan) despite different parents—both the lost souls of the children of Scarlet Witch and Vision from some storyline I've never read. As I've indicated, the series is deeply embedded in the mythos of the Marvel universe all long, but this is probably the point where it got a bit too complicated for me; there's a lot to keep up with. I wasn't too sure about Speed as a person, either; a bit too nasty for what I like in a superhero comic. He feels like a Geoff Johns creation, and that's not a compliment.

If there is a flaw in the opening twelve issues, it's that—as you can tell from my summaries—that they're all bound up in the mythologies of the characters themselves. The stories are about Iron Lad's history, Patriot's history, Hulking's history, and clearly building toward something about Wiccan and Speed's history. This is all fine in isolation, but it stops Young Avengers from feeling like it has an ongoing premise. What are these characters trying to do when they're not dealing with their own backstories? What good are they accomplishing in the world? That's what I like to see in my superhero comics, and it's not here. This feels more like a movie, not a premise for an ongoing comic book. As John Seavey says, good superhero concepts should be "storytelling engines," but the Young Avengers don't have one yet... even if I think they could.

Oddly, then, it's up to a totally different creative team to try to come up with one. The last story I read was the Young Avengers tie-in to the Civil War event, which was a crossover with Runaways. This is written by Zeb Wells and illustrated by Stefano Caselli. Civil War was about an attempt by the government to create a superhero registry; some superheroes were opposed (led by Captain America), some on board (led by Iron Man). The Young Avengers are opposed, but Cap won't let them get into action because they're still young and untrained. The government is rounding up unregistered superheroes, and when the Young Avengers hear that the "Runaways" have been targeted, they spring into action.

I haven't read Runaways, but the basic premise is explained here: they're kids that discovered their parents were members of a supervillain group called "the Pride" and, well, ran away. They don't want to be heroes or villains, they just want to be left alone. Unfortunately, the events of Civil War means they can't be. Of course, when they first meet the Young Avengers, there's friction, but the two groups soon learn to work together to escape the threat of a government that's gone too far. There are some interesting connections between the groups; for example, the Runaways have their own Super-Skrull who is at first excited and then disappointed to learn that Hulkling is his prince, but refuses to embrace his destiny.

|

Whoops.

from Civil War: Young Avengers & Runaways #3 (script by Zeb Wells, art by Stefano Caselli) |

As an introduction to an ongoing storytelling engine for the Young Avengers, Wells does a good job. Here they are not dealing with their own backstories, but they are earnest, inexperienced do-gooders, eager to help, especially help people they think are like themselves. As they learn, they are different from the Runaways; the Runaways don't want to help others, they just want to stay out of trouble. As the first person to write the Young Avengers other than Heinberg, he has a good handle on their characters. They're not really taken further here, but they all get good moments and feel true to themselves. I was surprised to particularly like how he writes Speed, who has a charming big-brother relationship with Molly, the youngest of the Runaways.

|

Just two juvenile delinquents having fun together.

from Civil War: Young Avengers & Runaways #3 (script by Zeb Wells, art by Stefano Caselli) |

Unfortunately, I didn't care for the art of Stefano Caselli; I don't know if I could quite explain why, but it has a vibe I associate with mid-2000s DeviantArt that is just not my style, and it leans into the grotesque a lot. Probably the dark, murky coloring from Danille Rudoni doesn't help; it's often hard to see what's actually happening.

Still, I had kind of expected the first non-Heinberg/Cheung Young Avengers tale to be bad, and this isn't bad at all. Indeed, it made me think I should have included Runaways to this series of posts... but no, it's long enough, and I don't want to move backwards anyway. It looks like Marvel did a four-volume "Complete Collection" series of trade paperbacks; this story is collected in volume three. Someday I'll go back and read the previous fortysomething issues so I can get the full context... but not today, I have enough going on right now!

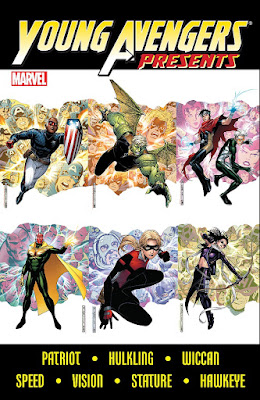

This is the first in a series of posts about the Young Avengers, Loki, and Hawkeye. The next installment covers Young Avengers Presents.