Best Short Story

6. "The Rose MacGregor Drinking and Admiration Society" by T. Kingfisher

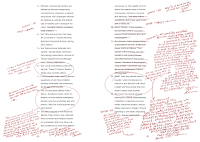

“Excuse me! I am a pooka! We drown people! None of this waiting around for them to die of a broken heart! We are efficient!”This was cute: a group of mythical creatures that usually tempt women and then leave them with broken hearts congregate to discuss Rose MacGregor, the woman who left them with broken hearts. I liked its playfulness with an old trope, but ultimately it's more cute than substantial.

5. "The Tale of the Three Beautiful Raptor Sisters, and the Prince Who Was Made of Meat" by Brooke Bolander

Such a long face! Don’t concern yourself a feather-tip about that poor horse, shining claw of my foot’s delight, for it opened like a generous man’s gut beneath Ceecee’s teeth and talons and not a hunk went to waste.A fairy tale about three raptors, a slightly dim prince, and a very clever princess. This was a fun read, and I liked the fairy-tale narrative voice, which hovered just on the right side of twee. It's fun to imagine the kind of fairy tales dinosaurs would tell. There were also good jokes about dinosaurs pretending to be human. Some of the gender stuff got a little too straightforward, though-- all of the women were clever, all of the men were stupid. I read fiction to be challenged, and that component of the story was too obvious.

4. "The Secret Lives of the Nine Negro Teeth of George Washington" by Phenderson Djèlí Clark

When George Washington wore Solomon’s tooth, he dreamed of a place of golden spires and colorful glass domes, where Negroes flew through the sky on metal wings like birds and sprawling cities that glowed bright at night were run by machines who thought faster than men.Set in a fantasy world, this story provides accounts of nine Negro teeth used by George Washington, each from a different person, each of which comes with some kind of magic, and each of which has some kind of effect on him. I would say that I admired the conceit more than I enjoyed the story per se, which is what made me give a slight edge to "A Witch's Guide to Escape," but I would say they're pretty much on par with one another.

3. "A Witch's Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies" by Alix E. Harrow

(There have only ever been two kinds of librarians in the history of the world: the prudish, bitter ones with lipstick running into the cracks around their lips who believe the books are their personal property and patrons are dangerous delinquents come to steal them; and witches).A librarian who is also a witch tries to help a boy living a rough life by giving him the books he needs, fantasies of escape (some exist in our world, like A Wizard of Earthsea; some do not but are of a recognizable type, like the fourteen-volume Tavalarrian Chronicles). I enjoyed it, but the narrative voice was at times a little twee. The fantasy element is slight, but deployed potently.

2. "STET" by Sarah Gailey

I read the weighted decision matrix they used to seed the Sylph AI. I learned to read it. Do you know how long it took me to learn to read it? Nine and a half months, which is some kind of joke I don’t get. The exact duration of bereavement leave, which is another kind of joke that I don’t think is very funny at all, Nanette in HR.This was a very cleverly told tale. It's a 100-word excerpt from a textbook on autonomous cars, with 800 words of footnotes, and then comments from an editor on the footnotes, and then rebuttal comments from the author. A story begins to emerge in all this, about a girl who died. It's cleverly told, and kind of touching, too. I think there's a real point in here, as well (though some of its fearmongering seems kind of overblown, along the lines of this Radiolab episode). The on-line version is neat, but the version in the print edition-- where the comments are handwritten-- is more effective.

1. "The Court Magician" by Sarah Pinsker

1. "The Court Magician" by Sarah PinskerThe first time he says the word, he loses a finger.As always, Pinsker nails it, with a clever concept well told. A kid magician from the streets is elevated to become the court magician, and goes from illusions to practicing real magic. Only, the real magic exacts a cost, as he slowly loses everything that he loves. But he keeps going on, because he must know how it works, always wondering if real magic is just another form of illusion. This one sucked me in and kept me going, a perfect little story.

Best Novelette

6. "The Thing About Ghost Stories" by Naomi Kritzer

Something had arrived in a padded envelope, and when I saw the return address, I tore it open eagerly. It was a first-off-the-press copy of The Stories We Tell in the Dark—my book.This is essentially just a ghost story. A very well-told ghost story, layered with literary details, but nonetheless not much actually happens in one sense, and things play out fairly predictably. But then again, the story is about the predictable nature of ghost stories, something the story itself sign-posts from the second paragraph, and I still felt tension as the story drew to a conclusion. As an academic, I appreciated the story gets academia largely right, and I found it really well done in parts. But it's still "just" a ghost story.

I set it down on the counter and just looked at it for a minute. It was published by the Indiana University Press and it looked really good: the cover image was a fog-shrouded forest, very spooky looking without appearing so much like a book for the layperson that no respectable folklorist would consider assigning it to their students in class.

5. "Nine Last Days on Planet Earth" by Daryl Gregory

“Beauty’s just”—he made explosion fingers—“joy in the brain, right? A flood of chemicals and, and, and—” What was the word? “Fireworks. Neuronal fireworks. We don’t logic our way to beauty, it hits us like a fucking hammer.”In 1975, strange alien seed pods fall to Earth, blanketing the world, and ten-year-old LT watches. The story jumps ahead in increasing intervals, covering LT's life in this new world. It's a great story, moving and unsettling at the same time, though maybe a little too obviously sentimental. I really enjoyed reading it, but I think that to be ranked higher, it would really need to do more with its sfnal element. Hugo-nominated short sf often feels reluctant to embrace its speculativeness, to prefer to tell literary fiction with speculative trappings. Which is fine, sometimes I like that approach a lot, but award-nominated stuff seems like it should be pushing harder.

4. "If at First You Don't Succeed, Try, Try Again" by Zen Cho

Leslie cleared her throat. “I didn’t get tenure.”An imugi (the worm-like nascent form of a dragon) keeps trying to ascend into a dragon and failing, but then it gets sidetracked when it meets a physics graduate student who ruined its most recent attempt. This was really good and kind of moving, and that I loved it but still ranked it down in fourth is a testament to how strong the novelette shortlist was this year. I think "When We Were Starless" and "The Last Banquet" both give me what I want out of sf/f a bit more, but this really got me in the heart, and it has some good jokes, too.

Byam had learned enough about Leslie’s job by now to understand what this meant. Not getting tenure was worse than falling when you were almost at the gates of heaven. It sat down, appalled.

“Would you like me to eat the committee for you?” it suggested.

3. "When We Were Starless" by Simone Heller

We told ourselves that we made a difference, that we shaped a world, but one look at this ruined vastness told the truth: we didn’t change a thing, and all our sacrifices were just to survive another day. It was enough, mostly, as long as we pretended it didn’t tear our hearts out.I struggled to rank this one vs. "The Last Banquet." "When We Were Starless," which follows a member of a sentient race of reptiles on an Earth polluted and abandoned by humanity, is more to my taste as speculative fiction; I love the world and imagery it conjurers up. But at times it is a little too immersive. Heller resists unnatural exposition quite successfully, which sometimes meant scrolling backward and forward while I tried to make sure I understood what happened, which occasionally undermined the story's emotional effect. But I did really like it. It has that aspirational tone of the best (to me) sf. We live in a world without stars, but we know they are there.

2. "The Last Banquet of Temporal Confections" by Tina Connolly

“You will see pain,” she said. “Not your own pain, but another’s. A moment of exquisite pain that someone else is suffering.”A really clever story, well told, where pastries, properly prepared with the right herbs, can invoke memories in the eater: Rosemary Crostini of Delightfully Misspent Youth, Fennel Flatbread of Sunlit Days Gone By, and so on. The story is told from the point of view of the pastry chef's wife, who serves as taster to the king, so that the pastry chef cannot poison the tyrant king. The story alternates between the present day (a Banquet of Temporal Confections) and the memories invoked by the pastries. A neat idea that enables a neat exploration of memory, with a clever conclusion. I do kind of wish there was more sf in the short fiction categories, but this was good fantasy.

No matter what you did, forty or fifty or a hundred years passed and everything became a narrative to be toyed with, masters of media alchemy splitting the truth's nucleus into a ricocheting cascade reaction of diverging alternate realities.The premise of this book sounds wacky if you try to explain it to someone: in an alternate reality where elephants are sentient, they are hired to replace the Radium Girls after it comes out how dangerous it is to work in the factories. The book alternates between elephant myths, a former Radium Girl hired to train them, and a researcher in the future, negotiating with the sovereign elephant tribes. But Bolander makes it work, and how. It packs a lot into its short length; it's about history, and labor, and our treatment of animals, and even Disneyfication. I complained in my write-up of "Last Banquet" that I wanted more sf, and I complained in my write-up of "Nine Last Days" that I wanted the sf elements to be more than props, and this story gave me exactly what I wanted on both accounts.

Best Novella

This is the only novella finalist I'd read before the ballot came out; in my review, I said it had a "muddled emotional throughline, an overly meandering plot, and too much happenstance." I liked each Binti novella less than the previous one, and this was the third.

It's like Holmes and Watson, except they're both women, and it's in space, and everyone's Vietnamese, and Watson is a former military spaceship traumatized by the death of her crew. I mean, why not? This had lots of great concepts (the Watson-analog spaceship makes money by brewing teas designed to manipulate the brain in specific ways), but as happens a little too often with novellas, I felt like the execution didn't completely live up to the idea; the emotional climax was a little subdued, and the mystery isn't really the focus, disappointingly.

The sequel to last year's winner is nowhere near as good. All Systems Red was a quick, engrossing action story with a distinct narrative voice. Artificial Condition is slow-moving (I wasn't sure what the story was even going to be about until I was a third of the way in) and the narrative voice is much more bland; I got much less of a sense of character off Murderbot than before. I didn't really get why it thought the so-called "asshole research transport" was an asshole; that seemed like a good joke that had been inadequately set up. I got more out of this than Tea Master, but even though Beneath the Sugar Sky was somewhat unfulfilling, it was at least trying to do something more than this ultimately hollow action piece.

The third Wayward Children book is definitely better than the second, but not as good as the first. In this one, four of the kids (all children who returned to Earth after visiting fantasy worlds via portals) go on a quest to resurrect a dead classmate, in order to ensure the existence of her future daughter-- who is on the quest with them. It's good, but not as good as it should be. McGuire's narrator likes to offer a lot of wise-sounding insight, but would benefit from being more attentive to character; each character has an elaborate backstory, but they often don't feel like they really matter, their actions in the present being kinda interchangeable, including the character who doesn't even want to be on a quest. It's entertaining, though (I like a portal-quest fantasy), and makes better use of the central concept than the second book did. Kept my attention more than Tea Master but didn't entertain me as much as Black God's Drums.

The best part of this book was its first-person narrative voice, told from the perspective of a black street urchin with an African goddess in her head-- in a steampunk New Orleans in a timeline where the Civil War ended in a draw, but New Orleans is neutral territory. The main character must get help from an airship smuggler captain when it turns out Confederate racists are building a superweapon in secret, in violation of the treaty. It's good fun, with strong worldbuilding and character. Its main weakness was that it felt a little set-up heavy, with not enough actually happening, and I dithered on how to rank it versus Tea Master, but ultimately decided I definitely want there to be a sequel, so Clark kind of gets away with it.

I liked this more than any of the other novellas on the shortlist this year. It has interesting worldbuilding (a post-environmental collapse where humans are beginning to reclaim the surface, but different people see it different ways), well-drawn characters, lots of interesting little details, a good sfnal hook, some sharp action sequences, and some good discussion of big ideas. I particularly liked the blending of the fantastic and the mundane: the main character works for an environmental reclamation organization, and has to submit a funding proposal... for a time travel project! But it was a bit too slow moving as the preparation of the grant proposal went on, and though I don't mind a story, especially an sf story, that leaves things open, several key questions posed at the story's beginning go unanswered. It's definitely doing more than any other novella finalist... but it feels more like the opening section of a novel in some ways.

1. No Award

Am I overly grumpy for doing this? Yes, but I am doing it anyway. 2017's novella line-up was outstanding, 2018's had a couple good ones, but 2019's ranges from terrible to above average, and I refuse to rank "above average" as my number one choice for a Hugo Award. Can I say what the problem is? Not really. It's tempting to blame Tor.com (all of these finalists bar The Tea Master and the Detective were their work), but they all have different problems. Gods, Monsters feels like a part of a novel, not a novella; Black God's Drums is a good action story that doesn't use its worldbuilding; the Wayward Children books probably should have stopped after the first one; Murderbot was fun before but this sequel was dull; and Binti is just bad. Several of them, though, suffer from the problem of coming up with good worlds or ideas, but failing to tell good stories about those ideas. I'd like to see a more diverse novellas shortlist in future, but given I only catch up on short sf with the Hugos, I won't be contributing to this myself.

Overall Thoughts

Short story was also a weak category this year; only "Court Magician" had the depth I would want of a Hugo finalist, even though many of the remaining stories were fine. I ranked a Sarah Gailey piece below in No Award in both 2017 and 2018, so I was wondering if it would happen again and if I just didn't get on with their writing, but 2019 shows they can impress me.

Oddly, I felt Best Novelette was highly competitive this year. In 2017, it had one clear frontrunner; in 2018, nothing set me alight. My theory was that the novelette is a fake form. There are no novelettes, just novellas that under-ran or short stories that weren't cut down. But 2019 has proved me wrong, with two excellent stories, three great stories, and one very good story. "Nine Last Days on Planet Earth" would have topped my ballot in 2018, but this year it must languish down in fifth!

I think Muderbot will win Best Novella; if not, it'll be Binti. The other two short fiction categories don't have any obvious top contenders, in my opinion, so I'll be curious to see what sifts to the top.

No comments:

Post a Comment